By Doyle M. Pace, originally published in the June 1993 Blues News

Sometimes in the late 1920s, a blind musician using the name of Arthur Blake migrated to the city of Chicago and took an apartment at the corner of 31st Street and College Grove Avenue. On most Mondays the flat was the site of a swinging musical and drinking party, attended by some of the Southside’s finest bluesmen.

In later years, one of the regular revelers, Little Brother Montgomery, reminisced about these gatherings: “We called them rehearsals. Usually we had them on Mondays when everyone was free. We’d all get together over at Blake’s place. Be a few piano players there—me, Spand (Charlie Spand), sometimes, Roosevelt Sykes. Guitar players like Blake and maybe Tampa Red or Big Bill Broonzy. We’d drink moonshine and trade songs. Everyone was just like family.”

Montgomery further remembered his host’s proficiency as a guitar player: “He kept good time and knew all the changes in all the popular songs back then. He would play it all and he was good in a band, too, but he mostly played blues and ragtime tunes. Blake loved the blues most. He always wanted us to play blues.”

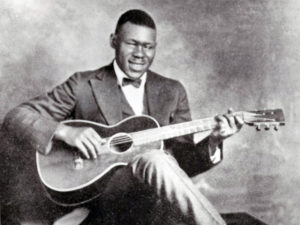

Blind Blake was a guitar virtuoso who had been recruited and brought to Chicago to record. His first record was “Early Morning Blues,” backed by “West Coast Blues.” The commercial success of this record prompted the company to records another 68 sides over the next 4 years. In fact, Blake’s success was an impetus for other record companies to seek out blues artists.

Before coming to Chicago, Blind Blake had spent many years playing music throughout the South and Southeast. He was seen by a lot of people in a lot of different places as he played minstrel and medicine shows, house parties, cakewalks, and street corners. His influence was considerable. In Bristol, Tennessee, he teamed up with guitarist Bill Williams for a while in 1921. Baby Take learned the “Police Dog Blues” from him in Elberton, Georgia. In 1926 Josh White encountered Blake in Charleston, West Virginia. In Atlanta, Blind Blake and Blind Willie McTell worked together and there are numerous other reports of people having seen and heard Blake from Florida to Ohio.

The style of guitar that Blake played wasn’t like the intense and emotionally-charged country blues of the Delta, but one of a ragtime dance style with a swinging beat. He was inventive, with a flair for improvisation. He could be subtle and understated or play with an ornate flourish. His extraordinarily fast and exciting three-finger picking technique used walking basses, boogie-woogie, and cross rhythms, as well as syncopated thumb rolls. Blind Blake was widely respected and admired by other guitar players; many tried to copy his style but with little success.

Reverend Gary Davis, known for his exiguousness in his praise for other musicians, said: “I ain’t yet beat Blind Blake on the guitar. I like Blake because he plays sporty.” Blake was one of the few guitarists who was able to excel in both ragtime and blues idioms. Researchers haven’t been able to come up with many factual details about Blind Blake’s life, so he remains something of a mystery. It’s not even known for sure when and where he was born.

Sheldon Harris’ Blues Who’s Who, a definitive source book for biographical data on blues people, indicates that Blake was born between 1890 and 1895, probably somewhere in the vicinity of Jacksonville, Florida. However, other sources give Tampa or the Georgia Sea Isles as his birthplace. It’s assumed that he did spend a considerable amount of time in Georgia and was familiar with the Geechee or Gullah dialect of the Sea Isles because, on his recording of an instrumental number, “Southern Rag,” he gives a spontaneous recitation in that dialect.

Even Blind Blake’s actual name is a matter of speculation, his friend and one-time partner Willie McTell claimed that his name was actually Arthur Phelps, but Paramount Records used the name Arthur Blake to get copy rights on his compositions. To add to the confusion, on various occasions he also used the names Billy James and Blind George Martin.

Blake’s death is no less mystifying. In 1932, after his recording career dwindled, mainly due to the effects of the Depression, Blake left Chicago with George Williams’ Happy-Go-Lucky Road Shows and was never heard from again.

April 20, 2015 update: Click here for the story of Blake’s grave which was located in 2011.