by guest author Perry Aberli

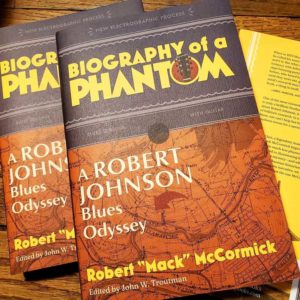

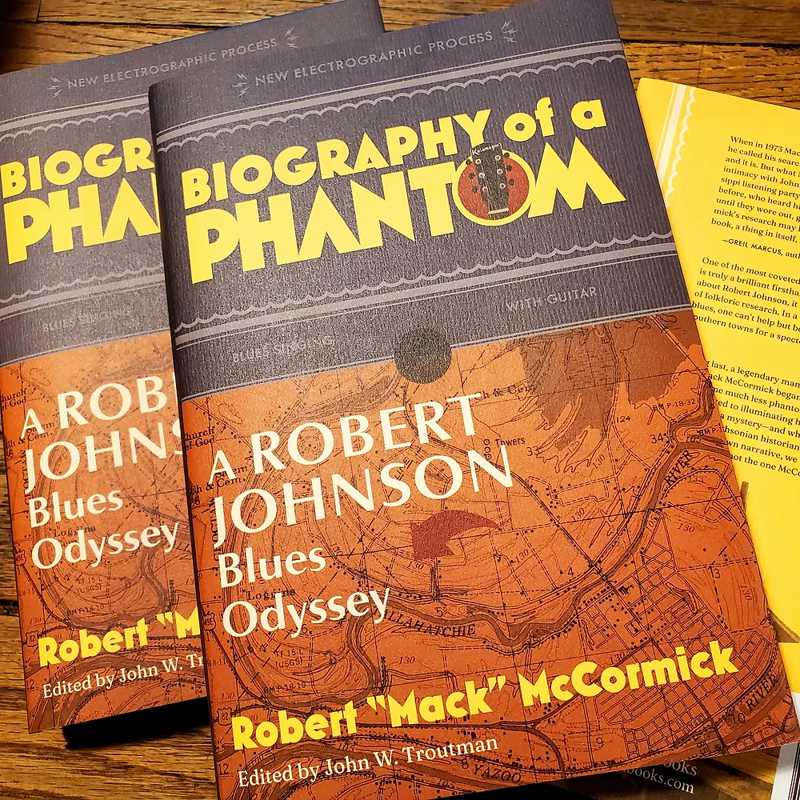

The classic bad joke starts with the line, “There’s good news and there’s bad news.” But it’s not funny when I cannot think of a better way to begin this. The good news? After almost 50 years, the work of Mack McCormick, Biography of A Phantom, has been released. The bad news? The very first page of the Editor’s Preface makes it clear that this is not a book about Robert Johnson, but:

An astonishing vantage point for considering the relationship between the material of the family of a renowned Black composer, singer, and instrumentalist who together experienced the trauma and terrorism of Jim Crow Mississippi; the manner by which a number of Johnson’s acquaintances, friends, and family, 30 years after the blues artist’s early death, were “discovered” by McCormick, a white Houston-based, self-taught folklorist and writer; the decision made by Johnson’s sisters, Carrie Thompson and Bessie Hines, to share details of Johnson’s life and more to McCormick and, then in consequence, and tragically for them all, the toll of their encounter (Phantom, p.vii). (I guess they don’t teach editors about run-on sentences anymore).

The editor, John W. Troutman, then advises the reader that, “Of course, while there are many phantoms in the book, Robert Johnson is not one of them.” (p. X). This is just the beginning of many retrojections of now known facts upon a search that was begun over 50 years ago.

For example, while we now have a glut of reissues of the complete Johnson body of music, multiple biographies, and photos; when McCormick began his search, the only available collection of Johnson’s song was the 1961 Columbia LP release, King of the Delta Blues Singers, (CL 1654). The LP was produced by Frank Driggs, who wrote the liner notes. “If you read the liner notes,” Driggs says, “you see next to nothing, because I just created a thing out of whole cloth when I wrote the notes because there was very little known about the guy.” (Robert Johnson at 100, Still Dispelling Myths, NPR Weekend Edition, May 6, 2011).

There were no photos; Johnson, at that time, was to those who listened to his music, a “phantom.” Troutman, it seems, would rather have the reader focus on the “phantoms” of racial terrorism, Jim Crow, power dynamics, theft, and cultural misappropriations which, he claims, are the tools and techniques of McCormick and other white field researchers of Blues.(He does, however, give Sam Charters a pass, citing Marybeth Hamilton’s characterization of Charters as exceptional within the Blues Mafia as an out-spoken advocate of studying the blues to expose entrenched social inequities and encourage support of the Civil Rights Movement (Notes: Editor’s Preface: ix, p. 197).

Further examples can be seen in Troutman’s ceaseless criticism of McCormick for what is now called “cultural insensitivity.” He also accuses him of using the imbalance in power between the races to coerce those whom he questioned. And, while the accusations of theft and cultural appropriation could more fairly be placed at the feet of white musicians and Steve LaVere, the editor is more comfortable in heaping them upon McCormick.

So, what’s going on here? It seems that, not being content with castigating and attacking McCormick and the Blues Mafia, in the Preface and Afterword, Troutman feels he must point out the deft censorship and revision he exacted upon McCormick’s work. Indeed, we really don’t know how much of the draft work, which McCormick apparently showed to Peter Guralnick, has been excised. Guralnick notes, in his Searching for Robert Johnson, that the draft had a section on Johnson’s trip to record in San Antonio, and that “Even in outline, it seems a peculiar odyssey, and it makes up a substantial part of McCormick’s projected book.” (Searching for Robert Johnson), Little, Brown and Company, Kindle Edition (p. 34). None of those critical events in Johnson’s life and legacy appears in Phantom. Guralnick clearly was shown a draft of the book that included much more of McCormick’s than Troutman has chosen to share. In this instance, the question is: what was so culturally inappropriate about the trip to San Antonio and the recording session there that would lead Troutman to exclude it?

This book is a much better read if one skips the self-serving Editor’s Preface and begins with the work itself. McCormick clearly intended this work to be a book for the general public, wanting it to be a kind of mystery story.

McCormick is a captivating writer: in the 4 pages of introduction to his work, he has you spell-bound as he summarizes the story he is about to spin before us. At its best, Phantom engages you in a personal way; you almost feel as if you were on the road with McCormick. Even though you know the answers he was yet to, or would never find, you share in his frustrations and joys as he hits bland walls or finds open doors in his search. McCormick’s descriptions of his journey, the geography, and the people are well crafted. It is, like any good mystery, a real page turner. But it’s frustrating because we know that Troutman has decided not to tell the whole story or show us the long promised pictures. The image presented of Johnson is still blurry; he is still a “ciph

[Note: You can purchase this book from Cathead book store in Clarksdale, MS. The KCBS does not receive any compensation from your purchase.]