By Doyle M. Pace, originally published in the December 1996 Blues News

By Doyle M. Pace, originally published in the December 1996 Blues News

“I got the blues from my baby,

Left me by the San Francisco Bay.

Ocean liner took her so far away.”

Anyone who was of the age of awareness in the I 960’s remembers San Francisco Bay Blues, an anthem of folk singers, but did they know that it was written by a jack-of-many -trades and a part time street singer who lived in the Bay area, by the name of Jesse “The Lone Cat” Fuller. Although Fuller had played music nearly all his life, he had remained virtually unknown, and he had never been able to earn a living from music until the folk trio, Peter, Paul and Mary had a big hit with his San Francisco Bay Blues. Subsequently, the song was covered by many other artists.

Fuller’s odyssey from his birthplace in Jonesboro, Georgia, to Oakland, California, is a fascinating saga. From the day of his birth, his life was harsh and full of troubles. He never knew who his father was, and his mother abused, starved, and abandoned him. He was twice badly burned by people who were supposed to be caring for him. First, an older cousin held his legs over a fire, and then a family that Fuller was staying with tied him in gunny sack and hung him in a fireplace because they thought that he was stealing lard to eat. Somehow, he survived these and other horrors and still ended up with a cheerful and upbeat disposition.

When he was only ten years old, Jesse Fuller walked out of the school house without even closing his books and began his life as “‘The Lone Cat.”

Fuller had a knack for music and without encouragement or support, he was able to nourish this talent until he was a passable musician. When he was seven years old, he made a mouth-bow. Later, he claimed that he had never seen a mouth-bow and the idea just came to him. (For those who don’t know, a mouth-bow is not unlike the home made bows for shooting arrows that kids use to make when they played cowboys and Indians, except the mouth-bow had a notch in one end. The notch is held against the mouth while the string is plucked, making a sound something like a Jew’s harp.) Next, Fuller fashioned a cigar-box guitar on which he tried to imitate the music that he heard at Saturday night frolics. This was all in the first decade of the twentieth century when the blues were new, and undoubtedly, Fuller, in his extensive travels, made contact with some of the Initiators of the East Coast brand of the blues.

Dr.Howard Odum, folklorist and early collector of African-American music, regarded the area southeast of Atlanta, centered around Newton County, to be a rich lode of what he termed “music physicaners”, wandering songsters and musicians who eked out a meager existence by going from one African-American community to the other, making music for tips and handouts. Several notable blues musicians lived In the part of Georgia where Fuller grew to manhood, including: Curly Weaver, Barbeque Bob Hicks, and his brother, Laughing Charley Lincoln, all of whom hailed from Newton County and all played the twelve-string guitar using a pocket knife for a slide, a style that Jesse Fuller used.

After striking out on his own, Fuller worked at an incredible assortment of jobs. He grazed cattle for ten cents a day; he worked in a buggy factory, a chair factory, a barrel factory and a paper mill. He delivered groceries, picked cotton, cleaned houses, worked on the railroad, all while he was still a teenager. When he was eighteen, Fuller earned the money for his first real guitar by picking up returnable bottles beside the railroad track and redeeming them for a penny apiece.

Fuller’s only real trouble with the law happened In Griffin, Georgia, when he was working for a junk man. He was arrested for buying scrap metal that had been stolen.

After being in jail for several weeks without any hint of a trial, Fuller decided that he had had enough of the Georgia justice system, so he picked the mortar out of the joints In the Jail’s brick walls until he had a hole big enough to crawl through and quickly departed from Griffin.

Fuller drifted into Atlanta when he was about twenty years old and got a job at the concession stand of a vaudeville theatre. Fuller related the story of how he got to know one of the female ‘performers.” With a gross voice, she was always hollering. “C’mere, little coco-cola boy’ –and could she sing.” The woman was the soon-to-be discovered Bessie Smith. From Atlanta, Fuller drifted on over to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where there were a lot of government jobs available making munitions to fight the Kaiser in World War I. It was here that he met his first wife, Curley Mae, but it was a troubled marriage from the start and didn’t last very long.

In 1918, Fuller went north to Cincinnati and got a Job working on the city street cars, but his rambling nature got the best of him when the circus came to town. He joined up as a circus roustabout and toured most of the United States and Canada.

While working this amazing assortment of jobs, Fuller never forgot his first love of singing and playing his twelve string guitar on whatever street corner he happened to find himself. Usually he made more money doing this than he did working his other job. In the early 1920’s, Fuller migrated to California.

His first work was as a vendor on Los Angeles streets selling novelty wooden snakes that he had carved. Next, he opened a shoeshine stand by the gate of United Artists Studio. He became popular with the movie folk and one of his best customers was the silent film star Douglas Fairbanks. Fairbanks took a liking to the congenial bootblack and often rewarded him with twenty dollar tips, as well as getting him small parts in movies. Fuller can be seen In East of Suez starring Pola Negri, Thief of Bagdad, The End of the World, and Hearts of Dixie. Film director Raoul Washington financed Fuller in a hot dog stand venture that was very successful financially, but his restless spirit once again took over and Fuller took a job with the Southern Pacific Railroad.

The railway gave him a pass that read, “for man and wife” and since he had no wife, Fuller decided to go back down South and get one. In Atlanta, he met Gertrude Johnson. In 1935, after a short courtship, they were married. The newlyweds returned to California, bought a modest house in Oakland, and settled into raising a family. On weekends, Fuller continued to play his guitar and sing on the streets as a solo act. He never wanted to join a band or play with other musicians. He said, “I was always off to myself–wouldn’t even hobo with nobody. I’m not biggity, but I’m just more comfortable alone.”

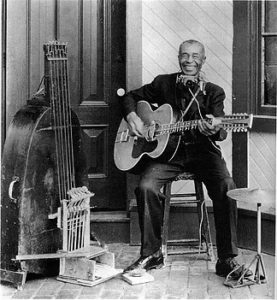

In the 1950’s, Fuller was approaching sixty and the rigors of a hard life of trouble, work and travel had done a job on his muscles and joints, so he decided to try to make music his livelihood. Still hankering to go it alone, Fuller began to formulate his concept of a one-man band. He invented a contraption that he called a ”fotdella.” After three or four revisions, his final concept was a six-foot tall thing that vaguely resembles a coffin or a bull fiddle. It was strung with six piano wires that, when struck by homemade hammers activated by pedals and springs and pushed through a guitar twelve-string guitar, blew a harmonica or sometimes a kazoo hung around his neck in a bracket, and somehow, even managed to get in a few licks on a washboard to complete his rhythm section. He even devised a tap dance routine to throw into the mix as a finale. The sound of this amalgamation was close to that of an old-time jug band.

Fuller liked to tell the story of the time when he heard Huddie Ledbetter (Leadbelly) on the radio boasting that he was the only twelve-string guitar player in America. With intrepidity, Fuller wrote to the radio station challenging Leadbelly’s assertions, and soon he got word from the Texas bluesman saying, “I’m coming, have a bottle of gin ready.” The two twelve-string guitar players jammed together few sessions.

Generally, though, Fuller remained mostly unnoticed by promoters and record producers, until he was heard by Chris Barber, a traditional jazz band leader from England. In 1960, Barber arranged for Fuller’s first trip abroad, where he was wildly received by British and European audiences. As his San Francisco Bay Blues started to become popular in this country, Fuller’s luck began to change. He started getting invitations to appear at folk festivals around the country, becoming one of the initiators of the 1960’s “blues revival.” He recorded several albums and appeared in a number of film documentaries and on the sound track of the movie, The Great White Hope.

However, his popularity remained the greatest in the British Isles, where he made three triumphant tours, appearing with the Animals and the Rolling Stones. Fuller continued to make the festival, college and club circuit in this country until his health began to fail in 1971. The Lone Cat’s restless spirit departed this earth on January 29, 1976.