By Doyle M. Pace, originally published in the February 1996 KCBS Blues News

In the southeastern part of the US, the decline of employment on farms in the decades following the Civil War saw a steady and increasing movement of people from the hinterlands to urban centers where industrialization was growing rapidly. Even though the disadvantages of segregation, Jim Crow laws, and the white supremacy movement were as bad in the cities as in the country, African Americans joined the migration rather than face starvation on the impoverished farms. Spartanburg and Greenville, South Carolina, which have only about 30 miles of sandy red clay soil separating them, became important industrial centers, drawing an influx of all manner of folks, including musicians of every stripe, black and white. In the decades between 1880 and 1920, many blues musicians lived in and around the Greenville-Spartanburg complex including Clara Smith, Reverend Gary Davis, and Josh White.

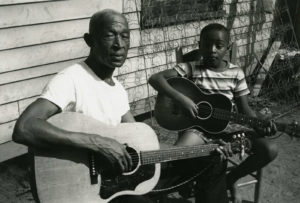

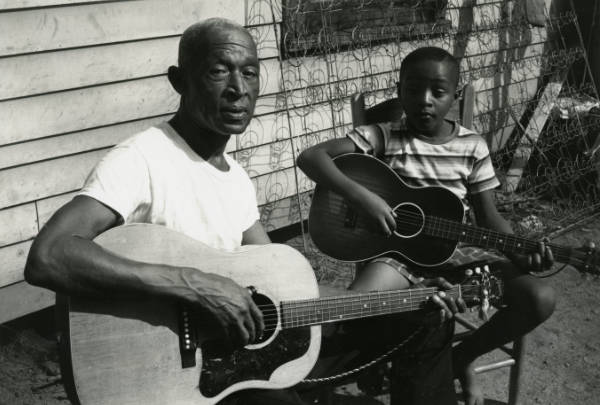

The best known of Spartanburg’s musicians was a songster, string-band member, and medicine show performer by the name of Pinkney (Pink) Anderson, who lived and performed there for 60 years. Pink was actually born some 40 miles to the south of Spartanburg in the town of Laurens, South Carolina. When he was about 8 years old, he learned to play the guitar from a neighbor in Laurens in an open-tuning style, using a pocketknife for a slide. It was after he came to Spartanburg as a teenager, however, that he learned chords and a more sophisticated picking style from an itinerant street musician from Georgia… Blind Simmie Dooley.

Dooley, who was nearly 20 years older than Pink, was a very demanding and thorough teacher who would not tolerate shoddy guitar playing. Fifty years later, Pink recalled that Dooley would “give him the devil” if he missed a chord. Pink played with Dooley whenever he was in town for as long as Dooley continued to perform. Eventually they even recorded together.

Like most Southern towns, Spartanburg had an African American string band that played for dances, picnics, and pig-pickings all around the Black sections of town and which also frequently performed for white social functions. Pink joined a five-piece string band soon after his arrival in Spartanburg and remained a member of the group for several years, playing with them when he was not on the road. In 1917, Pink joined Dr. W. R. Karr’s Indian remedy medicine company. This was to be his chief occupation.

As the larger and more elaborate to minstrel shows began to dwindle in the decade following the Civil War, the more rustic medicine shows begin to fill the breach, bringing to country people the only live professional entertainment many of them ever got to see. The heyday of the medicine show was from the 1880’s until WWII, with some continuing on into the 1950s. Pink Anderson worked with Chief Thundercloud’s show in the mid ‘50s.

The medicine shows usually had a larger city for their home base, where there was a larger talent pool from which to draw performers. In autumn, around harvest time, when of farmers had a little money to spend, the shows would roll out into the countryside, at first in a large horse-drawn wagons and later on flatbed trucks, stopping at county seats, villages, crossroads, stores, or any place where a crowd might gather. A show would be owned and led by a self-proclaimed “doctor”, a flamboyant and unabashed mountebank who acted as emcee, major domo, promoter, and a purveyor of the medicine… a rank concoction most commonly having as its chief ingredient a strong purgative dissolved in high proof grain alcohol.

The entertainers, of course, were used to drawing a crowd and loosen up the locals for the hard sell. A paltry little show may have only two or three performers, while the more elaborate vaudeville – like companies might carry as many as a dozen instrumentalists, singers, dancers, and comedians. The average size show, like Dr. Kerr’s, would include five or six players who could all sing, dance, and play several instruments. Curiously, in an otherwise strictly segregated society, a medicine show would frequently have a cast of integrated performers, and the audiences were also integrated. Otherwise, Dr. Kerr’s show had white musicians who traveled, played, and lived with Pink and other blacks.

Some very fine yet musicians, both black and white, cut their performing teeth on the medicine show circuit. Many, like Sonny Terry, Sleepy john Estes, Professor Longhair, Jim Jackson, Roy Acuff, Uncle Dave Macon, and Hank Williams went on to become major blues and country stars. “The father of country music” Jimmy Rodgers’ first job as a full-time performer was doing a “blackface routine” with a medicine show. It may be questionable whether the potent potion proffered by these fraudulent physicians was salubrious to the physical health of the rural folk, but the entertainment, no doubt, soothed many a weary psyche benumbed with its tedious and humdrum existence.

The medicine shows were also instrumental in spreading different styles of music from place to place and, after the advent of the blues, its licks and lyrics were circulated throughout the Southland by medicine show performers like Pink Anderson. Pink was already an accomplished guitar player, singer, and buck dancer when he joined the Kerr show and, from Dr. Kerr, he gained the showmanship that made him a consummate stage performer.

During the off season, when he was not traveling, Pink always returned to Spartanburg to play local gigs with his old teacher Simmie Dooley. The first time Pink was to record, and the only time Dooley recorded, was in 1928, when Dooley was nearly 50 years of age. It is unclear exactly how the recording session came about. Perhaps someone, possibly a music store owner, contacted Columbia Records and urged them to record that duo. In any case, one April morning, an agent from the record company picked Pink and Dooley up and drove them to Atlanta, where they cut four sides.

Both men played the guitar; Pink sang a lead on all but one of the numbers, and both men alternatively sang stanzas. The two sides, released on the first record in August of 1928, had a definite show circuit sound, but the other two were much more in the blues idiom. C. C. And O. Blues, composed and sung by Dooley as a tribute to the railroad that ran by his front door, had a good solid blues sound. Sales of their records with modest, but Columbia recognized Pink’s potential and asked him to return, but without Dooley. Not wanting to forsake his old friend and mentor, pink turned down the offer. He didn’t record again until 1950.

Dooley didn’t like to travel. He toured a couple of seasons with Pink on the medicine show circuit, but most of his time was spent on the streets of Spartanburg. He stopped playing in the 1930s but lived on until 1961. Pink continued with Dr. Kerr’s show until it folded in 1945. He toured with other shows for a few years, but by then the old-time medicine show was becoming an anachronism and fading from the American scene. While he was working at a fair in Charlottesville, Virginia, pink was recorded by Faulk music scholar, Paul Clayton, and eight sides were released by riverside records.

By 1957, Pink had serious health problems that forced him to curtail his musical career. In 1961, blues historian Samuel Charters located Pink in Spartanburg and recorded three albums of medicine show tunes, ballads, and blues. These albums brought Pink to the attention of folk music devotees and resulted in him getting a few jobs in colleges and coffeehouses, but he was too ill to revive his career. His last years were spent running an illegal drink house and of the hottest crap game in Spartanburg.

Pink Anderson never had a big recording contract, and he never became a “star,” but his contributions, like that of countless other journeyman blues musicians, played an important role in bringing us the universally loved musical experience that we called the blues.

Pink Anderson died on October 12, 1974.

(Article submitted by LaDonna Sanders)