By Doyle M. Pace, originally published in the February 1994 Blues News

By Doyle M. Pace, originally published in the February 1994 Blues News

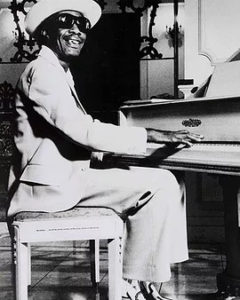

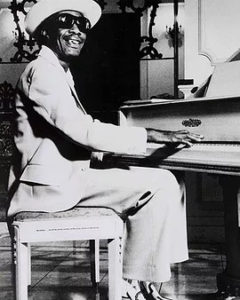

In October of 1993, New Orleans premier music club, Tipitina’s, officially changed its name to Professor Longhair’s Tipitina to honor the legendary piano player, singer, and composer who made the club his home base for a number of years before his death. This tribute to “Fess,” as he was affectionately called by his fans, was in conjunction with the dedication of a permanent memorial that features a cast bronze bust of Professor Longhair sculpted by New Orleans blues musician and artist Coco Robicheaux.

When it is completed, the memorial, located next to Tipitina’s at the corner of Napoleon and Tchoupitoulas Streets, will also include a photo-etched bronze sculpture of a standing Fess, with arms crossed, in front of a piano, and another image of him seated at his keyboard. The plaza landscape will have colored paving with the legend Professor Longhair Square sandblasted into the walkway, along with biographical information and selected verses from his songs.

Why all the hoopla over a piano player who never had a record the top of the charts, or never played to sellout crowds on a national tours, but who, in fact, seldom left the city and remained a little known outside the New Orleans area? There are several good reasons that the Professor was so revered by musicians and fans in the Crescent City. He was an accomplished piano player and singer and an electrifying entertainer. He was an innovator of New Orleans’ distinctive rhythm and blues sound, and he had an infinite influence on the next generation of New Orleans piano players. Fats Domino, Dr. John, and Allen Toussaint have all acknowledged their debt to the Fess. It was Toussaint who dubbed him the “Bach of rock.” His many compositions celebrating Mardi Gras have made him a veritable poet laureate of Carnival.

Mardi Gras in New Orleans is an incredible phenomenon that confounds description. It really has to be experienced: the parades, the incessant drums and blaring horns, the awesome masks and costumes of chimerical fabrication… The secret and private mystery of the krewes and the exotic names of Zulus, Comus, and Rex… Mardi Gras Indians, the dancing, prancing yellow Pocahontas and wild Tchoupitoulas… A teeming mass of variegated humanity is jammed together in a wild abandon of nonsense, color and music.

Everywhere during the Mardi Gras season, Professor Longhair’s composition “Go To The Mardi Gras” can be heard emanating from jukeboxes all over the city in a paean of welcome, bidding all to join in the frivolity. That song has become the anthem of Carnival, as well it should be, for the Professor’s song embraces all the teeming profusion of sensations that swarmed over the Crescent City in this season of misrule.

When Henry Roeland (Roy) Byrd was born on December 18, 1918, his parents were living in the sawmill town of Bogalusa, Louisiana, 60 miles north of New Orleans. However, they separated shortly after the baby was born and his mother took him to New Orleans when he was only two months old. Young Roy Byrd showed a natural aptitude for music and learned the fundamentals of the piano from his musically talented mother, but his real musical education came from hanging around the saloons on notorious Rampart Street which was, in those days, a refuge for barrel house piano players. Here he was inspired by some of the greats like Kid “Stormy” Weather, Tuts Washington, Champion Jack Dupree, and the obscure and mysterious Sullivan Rock.

Byrd left school in the early grades, forsaking formal education to pursue the life of a street entertainer. For a few years, he performed a solo act as a dancer, singer, and player of musical instruments of his own fashions. Then, in the early 1930s, he put together a small group of dancers and worked in various clubs in New Orleans, but, as the hard times of the Depression closed in, Byrd had to resort to doing whatever he could to make a living. He was a professional gambler for a while and, like his friend Jack Dupree, he took up boxing. Byrd even joined the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps. Finally, after the start of WWII, Byrd joined the Army and served until 1943.

He continued to work outside of music for a few years after his discharge but, by the late ‘40s, Byrd felt the urge to get back into the musical scene. He formed a small combo and started looking for gigs to play. In 1947 he was working at the Caledonia Inn when the owner of the joint, looking for a catchy name, started calling the group Professor Longhair and The Four Hairs. Byrd’s handle stuck, but, perhaps fortunately, the Four Hairs were soon forgotten. In fact, Fess renamed the combo the “Shuffling Hungarians” (an improvement?) to make his first recordings for the Star Talent label in 1949.

The next year he cut the famous “Tipitina”, which became a minor hit for him on the Atlantic label. Professor Longhair became a popular entertainer in New Orleans and, finding plenty of work in that city’s abundance of nightspots, he rarely left the area to perform. During the 1950s and ‘60s, he recorded for a variety of labels, but none of those sides had more than moderate commercial success.

By the late ‘60s, Fess had more or less stopped performing and slipped into obscurity, but in mid- ‘70s he started making a comeback. In 1977, thw Professor’s revivification was given a big boost when some of his friends opened a music club and named it “Tipitina’s” after his hit. His regular appearances at Tipitina’s and annual appearances at New Orleans’ Jazz & Heritage Festival brought the Professor’s popularity to its greatest heights in those last few years of his life.

Professor Longhair’s genius was in being able to take the many styles he heard all around him–blues, jazz, Caribbean, Cajun, Tex-Mex, Mambo, Rhumba, and Calypso–and blend them into a sensual musical gumbo that recollects for the listener the myriad flavors of his great city.