by guest author Dwight Hobbes

This is a good time to catch this classic movie and its look at the life and career of Leadbelly, one of the pioneers of blues music.

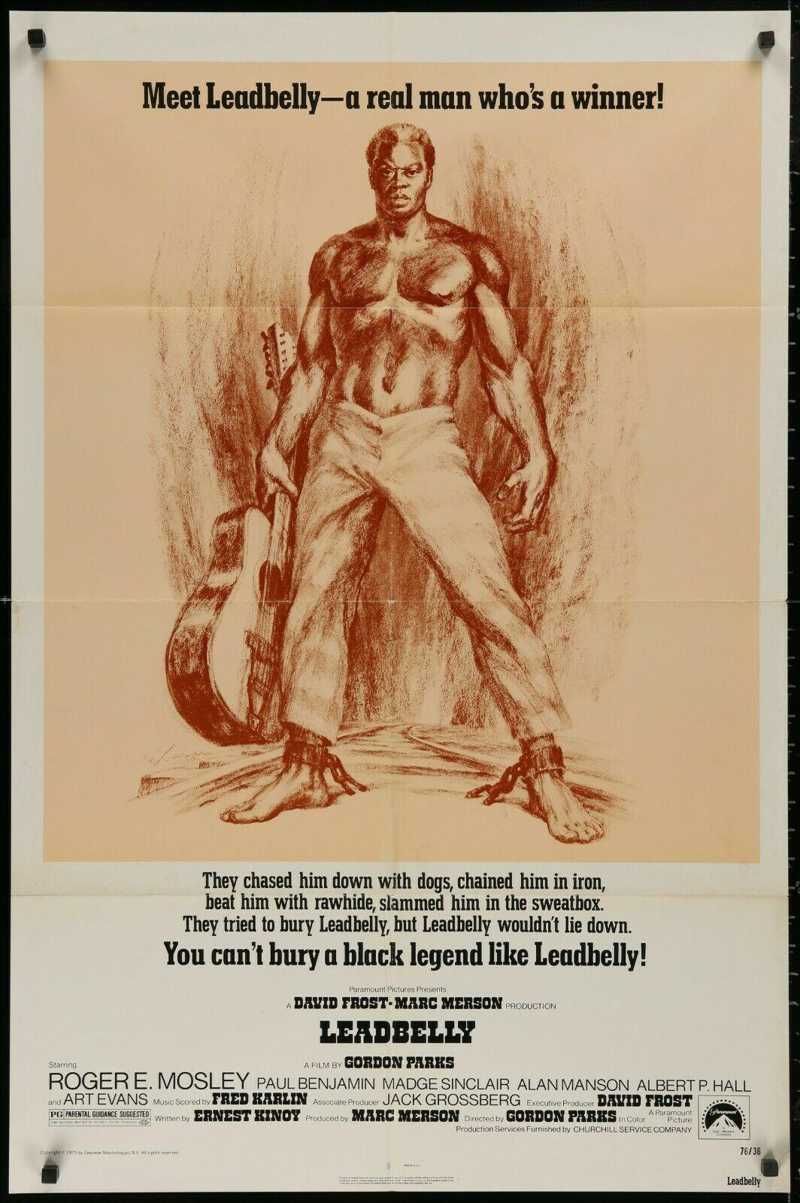

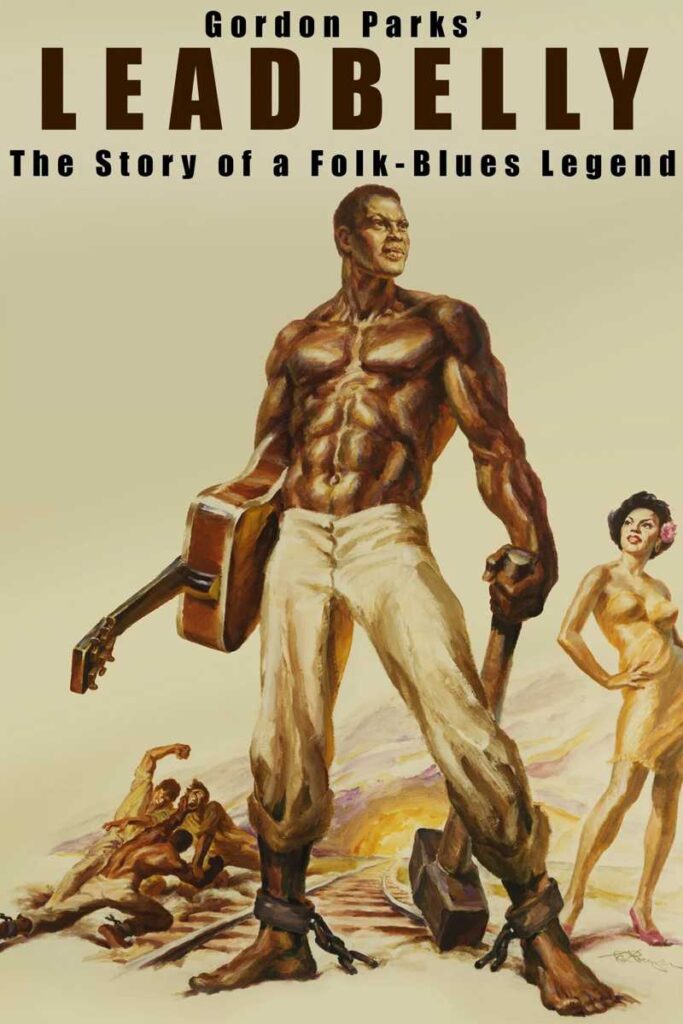

Gordon Parks’ Leadbelly (Paramount Pictures – 1976) is deeper than a well on a couple of levels. One, of course, chronicling the generally acknowledged Godfather of the Blues. We also glimpse rural and urban Black Americana circa 1930s. And we visit an era of cinematic breakthrough when Hollywood finally moved away from its demeaning ideal of maids, mammies, and shiftless steppin’ fetchin’ fools. You can’t make this film and have it be only about the genre, only about the music. It has to be about the people. Which it is, a remarkable achievement in the 70’s when movie makers marketed a new stereotype: soul brothas going upside The Man’s head and sistahs strutting around in shrink wrapped hot pants. Accordingly, Parks, who had directed Shaft and The Learning Tree, was well within his rights to pitch a bitch at Paramount Pictures’ promotion, and ads that he said made this cinematic groundbreaker look like Mandingo Returns.

The rich material could’ve been grittier, but you do see the threadbare lives of folks making do in harsh circumstances, and understand why they were happy as hell to put on their glad rags to break wild, hoist a glass, and shake a tailfeather at this or that makeshift after hours joint in the backwoods. There’s also a sanitized look at Shreveport, Louisiana’s nefariously renowned red-light district, St. Paul’s Bottoms. Between the afterhours shanties and ho’ houses, “musicianers” like Leadbelly and Robert Johnson earned a living without having to “Yassuh, boss” Mister Charlie or anybody else. It’s debatable how far afield Parks and screenwriter Ernest Kinoy (Victory at Entebbe, Buck and the Preacher) went off the facts. “Huddie was a bad man, as whites down there in the South would describe him, John Henry Faulk, who played Texas Governor Pat Neff, told the New York Times. “But his anger never took on the sullen, defiant way it was depicted in the movie. Instead, he was very solicitous, very eager to please. A threatening gesture at a white man would have indeed cost him his life.” Parks’ own agenda held sway. “Leadbelly may not have struck at whites the way he did at Blacks but had him doing it in the film because they deserved it. Hell, all the other movies about whites are so over balanced the other way. Why are they being such sticklers for authenticity?”

Ultimately, Leadbelly places the blues in perspective. You get a feel of the climate that spawned this part of American culture. For instance, a blues story wouldn’t really be about blues without authentically portraying the people. For example, the rural Louisiana home when the local redneck law comes calling about some trouble Huddie got himself in. Veteran character actor, Paul Benjamin (Hoodlum, The Five Heartbeats) is Wesley Leadbetter, a loving steam man hard on his son so “Mr. Charlie” doesn’t come down harder. Lynn Hamilton (Sanford & Sons) plays Sally Leadbetter, a strong gentle woman having her husband’s back, quietly worried which way things will break as he stands his ground, calm, steadily eye-to-eye with this white sheriff. William Wintersole (The Young & the Restless, Star Trek) gives Sheriff Gibbons gravity in this razor’s edge moment.

We trace his life from leaving the Leadbetter farm to haphazardly making his way through life, earning a serious reputation and serving prison sentences (between county jails and state penitentiary), he may well have spent as much time locked up as he did a free man. Eventually leaving his mark, most times going through hell to do it.

Huddie knocks up a gal and blows town, and lands in the fast, big city life in Shreveport, a bumpkin woefully out of place. Doesn’t take long to luck up and get in the good graces and in the bed of street madam, Miss Eula, played to a flinty tee by Madge Sinclair (The Lion King, Roots). When she tries to keep him on a short leash, he ups and moves around again. Their reunion, years later, both fallen on hard times, is bittersweet.

Headed for Silver City, catching a train, he unwittingly brawls with a blind man, Blind Lemon Jefferson, played by Art Evans (A Soldier’s Story). They strike an accord and team up, rousing about and playing together. Jefferson introduces him to the 12-string and, from there the rest, as they say, is history.

Roger E. Moseley was the affable, resourceful T.C. — the helicopter flying sidekick to Tom Selleck on Magnum, P.I. Contrast that with his portrayal of Huddie Leadbetter, country as cornflakes, longer on personality and sex appeal than common sense, and quick to go upside someone’s head. Also, on hand are James Brodhead (Little House on the Prairie) as John Lomax, largely credited with discovering Leadbelly, swinging a sledgehammer in the rockpile at Angola Penitentiary, Alber Hall (Malcolm X), Vivian Bonnell (The Women of Brewster Place), and Ghostbusters’ Ernie Hudson.

Tide Harris does a nice job of supplying Leadbelly’s vocals and Art Evans has a great voice. On guitar: Brownie McGhee, Dick Rosmini and, for “Go Down, Ol’ Hannah.” The repertoire is a baker’s dozen, including The Midnight Special, Cotton Fields, Goodnight Irene and Bring Me a Lil’ Water, and Silvy.” Bear with the picture quality as it has a somewhat fuzzy focus, like you would say, static on an old 78. After awhile you won’t even notice it, because this is a valuable artifact. What blues lovers should walk away with after viewing Leadbelly is that this revered originator of blues music is deservedly honored.

[Ed. note: read more about Gordon Parks and his Kansas City-area connections on Wikipedia.]