By Doyle Pace, originally published in the November 1995 Blues News

By Doyle Pace, originally published in the November 1995 Blues News

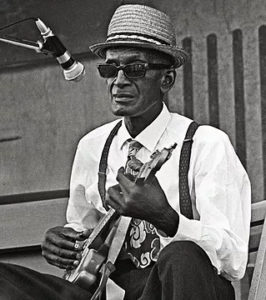

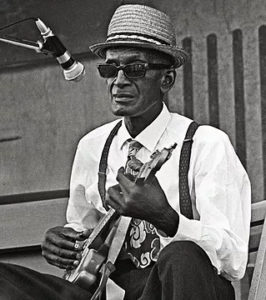

When the documentary filmmaker David Blumenthal rediscovered Sleepy John Estes in 1962, the former blues great was destitute and living in a tumbled down shack in the middle of a cotton field outside the town of Brownsville, Tennessee. This was where his musical career had begun and 50 years before. Blumenthal was elated with his find because Estes had been presumed to be long since dead, even by many other blues musicians.

Sleepy John Estes wasn’t born quite in the Mississippi Delta, but his early biography has the familiar sameness as many of the Delta bluesman of his generation. He was born into a cotton farm sharecropper family; his father taught him his first chords; and his first gigs were at fish fries and house parties. Jon Davis passed this was born on a farm near Ripley, Tennessee, on January 25, 1904. Ripley is about 50 miles northeast of the Delta, if we accept the fact that the Delta begins in the lobby of Memphis’ Peabody Hotel. When he was about 11 years old, the Estes family moved to a farm near the larger town of Brownsville.

He got the nickname Sleepy from the fact that he would frequently doze off, often at the most inopportune times. The malady is said to have been caused by a blood pressure condition that plagued him all his life. It was in Brownsville that Estes found his mentor in a local character and blues man named Hambone Willie Newbern. Newbern was known for his rendition of the Delta barrelhouse favorite Roll And Tumble Blues. Newbern made a few recordings in the late 1920s, including the first waxing of Roll And Tumble, but mainly his career consisted of playing on the street corners of Brownsville and Memphis. Young John Estes learn the rudiments of guitar playing from Newbern and frequently accompanied the older musician to gigs. In fact, Estes’ guitar playing never developed much beyond the basic rhythmic, strumming style, but yet was well suited to his high pitched wailing vocal style that Big Bill Broonzy once described as “crying the blues.”

To compensate for his lack of virtuosity as an instrumentalist, Estes always managed to have exceptional sidemen. In 1919, he met up with a young mandolin player, James “Yank” Rachell, and they started playing together. Rachell, who was a Brownsville native, is said to have traded one of the pigs on his father’s farm for his first mandolin and went on to become a leading exponent in an elite group of blues mandolin players. Rachell had also served an apprenticeship with Hambone Newbern, during which time he developed the mandolin technique that enabled him to reach difficult blue notes on a rather limited instrument. Rachell, who is well into his eighth decade, can sometimes still be seen performing his mandolin magic out blues festivals [Editor’s update: Rachell died in 1997].

Estes and Rachell started playing farther and farther from Brownsville until they were ranging as far as Memphis, some 60 miles to the southwest. Here, they sometimes teamed up with Jab Jones, a jug and piano player and a veteran of various Memphis jug bands. The trio of Estes, Rachell and Jones called themselves the Three J’s Jug Band when they played Handy Park and the joints on Beale Street, especially the Blue Heaven Club, where they had a regular gig. Eventually, they were noticed by Victor Records’ Ralph Peer, who set up a recording date for them in September of 1929.

They cut four sides, with Estes doing the vocals and guitar and Rachell and Jones accompanying him on mandolin and piano. One side was Diving Duck Blues, Estes’ version of the old folk ditty, and Rye Whiskey, that has become a blues standard. For another cut, The Girl I Love She Got Long Curly Hair, Estes borrowed extensively from his old teacher Willie Newbern’s signature song Roll And Tumble Blues, using his tune, rhythm patterns and some of the lyrics.

Not long after the Victor sessions, Rachell left Estes and went back to farming. Fortunately he did resume his musical career a few years later, and he and Estes eventually got together again, 30 years later.

Meanwhile, Estes had found another partner in Hammie Nixon. Nixon was only 12 years old when Estes first heard him playing harmonica at a country fish fry. He was immediately impressed with the melancholy and soulful sounds coming from the boy’s mouth harp. Estes prevailed on Hammie’s mother to allow the boy to a company him when he was playing around Brownsville and Memphis. A lifelong relationship grew between the two, not just eight musical partnership, but also a profound friendship.

After Yank Rachell’s departure, Estes and Nixon continued to the Beale street clubs, but the grim economic conditions brought on by the Depression forced them to go back to farming to make a living. However, since conditions on the farm weren’t much better, if any, than being on the road, in 1931 Estes and Nixon hopped a freight to try their luck in Chicago. They played street corners and house rent parties. In 1935 they recorded in Chicago for the Champion label and two years later Victor Records producer Mayo Williams signed them for his label.

Estes had always been a prolific songwriter, and by the mid-‘30’s he had matured as a composer and a storyteller, contributing a wealth of material that has become a part of the collective blues repertoire. As subject matter, he drew from his own everyday experiences, and many of his best songs are really vignettes of his life. In one of his best known numbers, Floating Bridge Blues, Estes describes a near death experience he had as a result of an accident:

“They dried me off and they laid me in the bed.

They dried me off and they laid me in the bed.

Couldn’t hear nothing but muddy water running through my head.”

In a Working Man Blues, he indulges in some social commentary by criticizing the new industrial order because he felt new machines were taking the jobs of farm workers. Lawyer Clark Blues, incredibly, is a paean to a lawyer!

Estes never became a regular on the south side Chicago club scene, and he and Nixon had to continue traveling extensively throughout the ‘30’s, usually by hoboing around and playing wherever they could.

They even spent some time with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels and Dr. Grimm’s Medicine Show before they finally returned to Brownsville in 1941. Except for two short recording sessions in 1950 for the Ora Nelle label in Chicago and Sam Phillips Sun label in Memphis, both Estes and Nixon were out of the music business for the next 20 years.

When Estes was at a small boy, he lost the sight of his right eye in an accident and, over the years, his other eye deteriorated until he became totally blind by 1950. Being unable to work, he spent the next decade in abject poverty. However, as a result of Blumenthal’s fortuitous find, Estes’ fortunes increased and he was able to spend the rest of his days in relative comfort. He was included in Blumenthal’s 1962 documentary Citizen South – Citizen North, which in turn brought him to the attention of the folk revivalists. Estes was promptly signed to a contract with Delmark records and subsequently recorded for several other labels over the next 15 years, including Vanguard, Adelphi, Fontana and Folkways.

The first concert he played after his reentry into music was at the University of Illinois, followed by one at Harvard. So began a new career for the 52 year old Sleepy John Estes, playing colleges, and coffeehouses and folk festivals. His old friend Hammie Nixon accompanied him as a companion, guide and musical partner. Sleeping in comfortable hotels and a traveling by airplane certainly was quite a contrast to their first musical career. They went to Europe with the American Blues Festival group in 1964 and 1966 (where Yesterday’s Blues saw them in Germany), and Estes and Nixon’s last tour was a trip to Japan in 1976.

Sleepy John Estes suffered a stroke and died on June 5 1977. Hammie Nixon continued to perform as a solo act and as a member of the Beale Street Jug Band until his death on August 17, 1984.